Bless the Lord, O my soul,

And forget not all his benefits,

Who forgives all your iniquity,

Who heals all your diseases,

who redeems your life from the Pit

Psalm 103

This above psalm was read at the beginning of an 1887 Board meeting for the Home for Friendless Women. I stumbled across this charity while interning at the Filson Historical Society this semester. It’s hard to imagine this would be a go-to name for an organization nowadays, but there was a time this was a common euphemism for poor, unmarried, pregnant women. Louisville’s Home for Friendless Women began at 512 West Kentucky St. (later the site of the Salvation Army Susan Speed Davis Home and Hospital, and currently the Crimes Against Children Unit of the Louisville Metro Police), and it opened May 19, 1876 with the help of Susan Speed Davis. It operated until 1919.

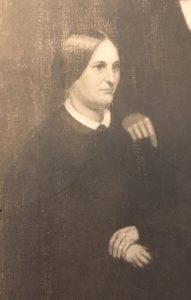

Susan Speed Davis, from the Speed Family Portrait,

Filson Historical Society Photograph Collection.

The admission logs, minutes from the Board meetings, newspaper clippings, and letters addressed to the women who ran the home (referred to, rather unfortunately, as “Madames” in one letter) offer insight into both Victorian society and vocabulary. Many women came to the Home from “houses of ill fame.” In fact, in one letter the charity was referred to as “The Home for Fallen Women.” Once admitted into the home, the women were often referred to as “inmates” and needed permission to leave the house, although I’ve since learned that “inmate” was simply a way to refer to a group of people living together in a house.

One goal of the Home was to help the pregnant women find respectable homes (their words) to work in after their child was born and also to encourage the women, often referred to as girls, to lead Christian lives. From reading the Board meeting logs, it becomes clear this was not always what happened. In one entry, a woman is reported to have “gone back to a life of sin.” Another woman was expelled from the Home for profane language and yet another, it was feared, had returned to “evil causes.”

It’s still very early in my research, so my final project is still taking shape. Whether this will be a non-fiction project about the Home told in a series of essays or more of a historical fiction approach, I haven’t yet decided. But there are certain characters that emerge from these pages, stories of women who refuse to be molded or labeled as fallen, and it’s their stories that I find myself thinking about the most.

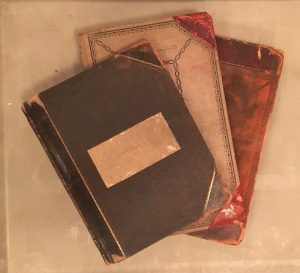

Home for Friendless Women Ledger Books.

Home For Friendless Women Records,

The Filson Historical Society

For example, in one memorable scene from August 2, the inmates were called before the Board and sternly warned to be mindful of their conversations in private, which led to several women confessing (tearfully I imagine, although I might be projecting) to using improper language in private. The President then read aloud the rules of the Home and asked all who would follow the rules to stand; all but one rose. The woman who refused to stand, Belle, had been mentioned in previous entries. Earlier in the year, the women on the Board had praised her efficient work in the laundry and wanted to buy her new clothes, but they worried this would incite jealousy among the other inmates, and so they decided it wise to gradually add articles to her wardrobe. By August, Belle is being mentioned again, only this time for “misconduct” and “pernicious influence” on another inmate. It came as no surprise to read that by the time the next meeting rolled around, Belle had been expelled from the Home.

These women often lacked agency in their lives – sometimes they kept their children, sometimes they didn’t. Sometimes they came willing to the house, other times a parent or doctor brought them. There are casual mentions of women being sent to insane asylums and of couples adopting the children of these women. From reading Stone Heart and Shannon this semester, I’m interested in the idea of providing a voice to a group who were both helped and held down by the rules of Victorian society.